博文

“逻辑”与“逻辑学”(5) -- “逻辑学”的理性或经验性(“量子力学的逻辑”为例)  精选

精选

||

[敬请读者注意] 本人保留本文的全部著作权利。如果哪位读者使用本文所描述内容,请务必如实引用并明白注明本文出处。如果本人发现任何人擅自使用本文任何部分内容而不明白注明出处,恕本人在网上广泛公布侵权者姓名。敬请各位读者注意,谢谢!

“逻辑”与“逻辑学”(5) -- “逻辑学”的理性或经验性(“量子力学的逻辑”为例)

程京德

在人类所有文化活动的语言文字交流当中,“逻辑(λογική/λόγος , logique, Logic, logik, 論理[ろんり])”是最频繁地被用到的词汇之一,同时也是最多义/歧义的词汇之一。那么,到底什么是“逻辑”?其涵义究竟为何?对于这个问题,随便问十个人就可能会得到十个不同的回答。另一方面,尽管希腊语及法、英、德语等中“逻辑”和“逻辑学”通常都是用一个词汇来表达,但是在日语和中文中,“逻辑”和“逻辑学”都可以是(但未必一定是)用两个词汇来清晰地区分表达的。所以,在理解世界各主要语言文字表达的时候,都有基于具体的上下文语境来区分清楚“逻辑”和“逻辑学”的需要。实际上,在人类所有文化活动的语言文字交流当中的绝大多数场合,“逻辑”一词并非指称“逻辑学”而是指称各种各样的具体场景,其中有些场景甚至很难说与“逻辑学”相关。本文试图澄清“逻辑”与“逻辑学”的诸多异同[1-4]。

具体的“逻辑”,应该是经验的。而作为抽象科学的“逻辑学”,其本性究竟为何?这是一个逻辑哲学中长期讨论的问题。本文仅以“量子力学的逻辑”为例,介绍相关讨论。

“逻辑”是经验的

“在一般语境下被正确地使用时,作为一种抽象性质或者评价标准,‘逻辑’通常可以指的是陈述(请注意,并非思维!)的清晰性、合理(合规)性、或者一致(无矛盾)性;作为一种具体事项,“逻辑”通常又可以指某个客观逻辑规律、某个推理过程或者推理场景。”[1]

“如果某个人所陈述的推理过程是清晰的、合理(合规)的、一致(无矛盾)的,我们通常会说他/她的陈述是‘合乎(有)逻辑’的;相反,如果某个人所陈述的推理过程不清晰、不合理、跳跃性大、前后矛盾,我们就会说他/她的陈述是‘不合(缺乏)逻辑’的。对于某个具体的客观逻辑规律、推理过程或者推理场景,我们会说‘这个逻辑’、‘那个逻辑’、‘XXX的逻辑’等等。”[1]

所以,“逻辑”,当被用于指称某个具体事物时,一般是依赖于某个具体场景,亦即,是经验的。

“逻辑学”是理性的还是经验的?

“逻辑学”出自于对各种具体场景“逻辑”事例的系统性研究,以区分正确的“逻辑”和不正确的“逻辑”,以及寻求一般性判别标准。所以,从古希腊亚里士多德时代起,在很长时间内,“逻辑学”都一直被认为是理性的、先验的,被当作用之四海而皆准的“绝对真理”(“the one true logic”, “the one right logic”)来探求追究。

历史上,关于“逻辑学”的本性究竟是理性的还是经验的,哲学家们(包括休谟、康德、胡塞尔、佛雷格、罗素、维特根斯坦、卡尔纳普等大家)都是在一般意义下在某种抽象程度下讨论。然而,美国哲学家普特南(Hilary Whitehall Putnam, 1926-2016)在1968年以“量子力学的逻辑”为具体实例提出了一个可以说是“惊人的”问题:“逻辑学是不是经验的?(Is logic empirical?)”[5,6]

何谓“量子力学的逻辑”?

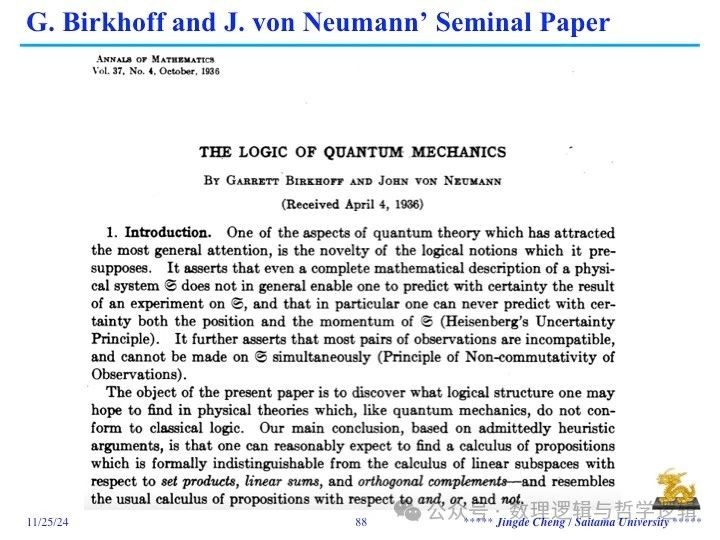

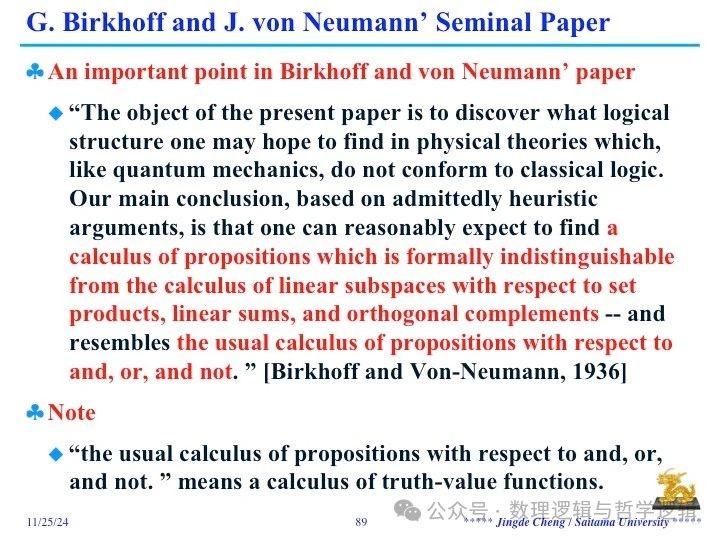

作为对于量子力学的数学/逻辑解释,“量子力学的逻辑”最初是由美国数学家伯克霍夫(Garrett Birkhoff, 1911-1996)和冯诺依曼(John von Neumann, 1903-1957)于1936年提出的[7]。

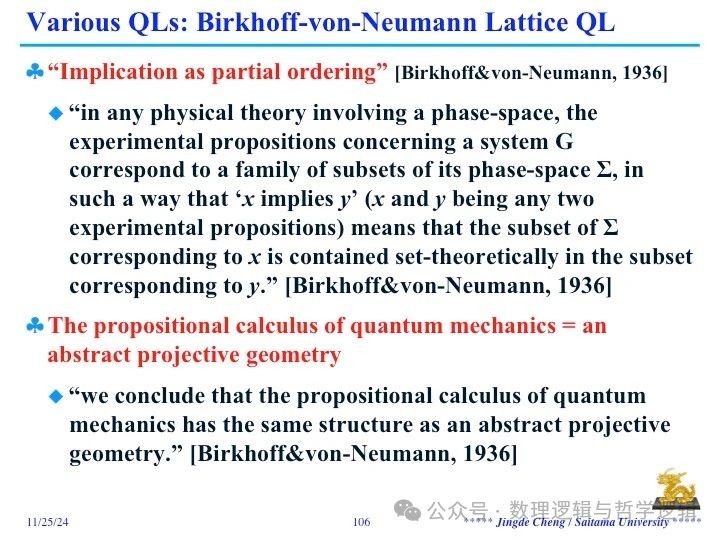

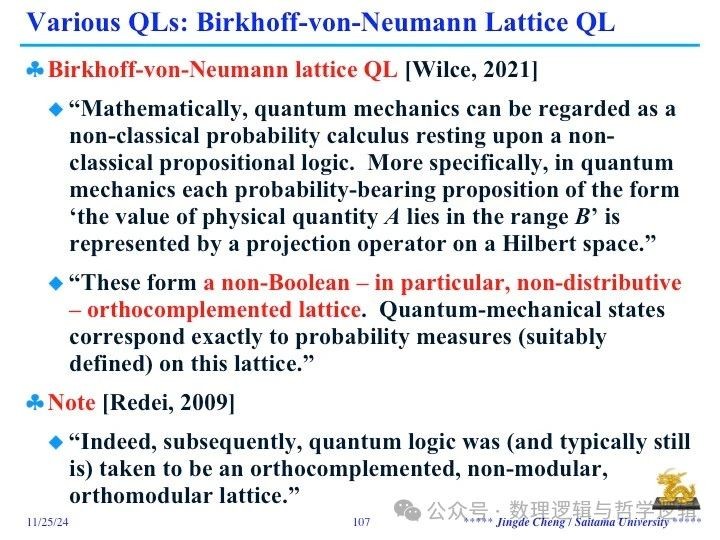

“量子力学的逻辑”之本质特征,如果用伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼文章中所强调的话来说就是,“我们得出结论,量子力学的命题演算与抽象射影几何具有相同的结构(we conclude that the propositional calculus of quantum mechanics has the same structure as an abstract projective geometry.)”[7]。此处所谓的“抽象射影几何”是一个“非分配的正交补格(a non-distributive orthocomplemeneted lattice)”。“事实上,后来量子逻辑被认为是(现在通常仍然是)一个正交补、非模、正交模格。(Indeed, subsequently, quantum logic was (and typically still is) taken to be an orthocomplemented, non-modular, orthomodular lattice.)”[8]。

伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼的结论实际上应该包含两个部分,首先是,从量子力学抽象出其命题演算,其次才是,证明量子力学的命题演算与抽象射影几何具有相同的结构。

让我们先来看看伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼是如何得出上述结论的。

“对物理系统 G 的‘观察’通常可以描述为记录各种相容测量的读数。因此,如果测量用符号 u1, …, un 表示,则对 G 的观察相当于指定与不同 uk 相对应的数字 x1, …, xn。因此,关于 G 的预测的最一般形式是,通过实际测量 u1, …, un 确定的点 (xl, …, xn) 将位于 (xl, …, xn) 空间的子集 S 中。因此,如果我们将与 G 相关的 (xl, …, xn) 空间称为其‘观测空间’,那么我们可以将与任何物理系统 G 相关的观测空间的子集称为关于 G 的‘实验命题’。(It is clear that an ‘observation’ of a physical system G can be described generally as a writing down of the readings from various1 compatible measurements. Thus if the measurements are denoted by the symbols u1, …, un, then an observation of G amounts to specifying numbers x1, …, xn, corresponding to the different uk. It follows that the most general form of a prediction concerning G is that the point (xl, …, xn) determined by actually measuring u1, …, un, will lie in a subset S of (xl, …, xn)-space. Hence if we call the (xl, …, xn)-spaces associated with G, its ‘observation-spaces,’ we may call the subsets of the observation-spaces associated with any physical system G, the ‘experimental propositions’ concerning G.)”[7]

“量子理论与经典力学和经典电动力学有一个共同的概念,这就是数学‘相空间’的概念。按照这个概念,任何物理系统 G 在每一个时刻都假设与固定相空间 Σ 中的一个‘点’ p 相关联;这个点应该在数学上表示 G 的‘状态’,而 G 的‘状态’应该可以通过‘最大’观测来确定。此外,在时刻 t0 与 G 相关联的点 p0 ,结合规定的数学‘传播定律’,可以确定之后的任何时刻 t 与 G 相关联的点 pi ;这一假设显然体现了数学因果关系原理。因此,在经典力学中,Σ 的每个点都对应于 n 个位置和 n 个共轭动量坐标的选择。... 在量子理论中,Σ 的点对应于所谓的‘波函数’,因此 Σ 又是一个函数空间 -- 通常被认为是希尔伯特空间。(There is one concept which quantum theory shares alike with classical mechanics and classical electrodynamics. This is the concept of a mathematical ‘phase-space.’ According to this concept, any physical system G is at each instantly hypothetically associated with a ‘point" p in a fixed phase-space Σ; this point is supposed to represent mathematically the ‘state’ of G, and the ‘state’ of G is supposed to be ascertainable by ‘maximal’ observations. Furthermore, the point p0 associated with G at a time t0, together with a prescribed mathematical ‘law of propagation,’ fix the point pi associated with G at any later time t; this assumption evidently embodies the principle of mathematical causation. Thus in classical mechanics, each point of Σ corresponds to a choice of n position and n conjugate momentum coordinates ... in quantum theory the points of Σ correspond to so-called ‘wave-function,’ and hence Σ is again a function-space -- usually assumed to be Hilbert space.)”[7]

于是,一个量子物理系统 G 的状态就被对应到一个希尔伯特函数空间 Σ。并且在定义了任意观测空间的子集 S(或“实验命题”)的“数学表达”,就是指 G 的相空间 Σ 中所有点 f 的集合之后,可以得到:

“(1)任何实验命题的数学表达都是希尔伯特空间的封闭线性子空间;(2)由于量子力学的所有算子都是厄米特算子,任何实验命题的否定的数学表达是该命题本身的数学表达的正交补;(3)对于给定类型的物理系统的两个实验命题 P 和 Q,以下三个条件是等价的:(3a) P 的数学表达是 Q 的数学表达的子集。(3b) P 蕴涵 Q -- 也就是说,只要可以确定地预测 P,就可以确定地预测 Q。(3c) 对于系统的任何统计整体,P 的概率最多等于 Q 的概率。((1) that the mathematical representative of any experimental proposition is a closed linear subspace of Hilbert space (2) since all operators of quantum mechanics are Hermitian, that the mathematical representative of the negative of any experimental proposition is the orthogonal complement of the mathematical representative of the proposition itself (3) the following three conditions on two experimental propositions P and Q concerning a given type of physical system are equivalent: (3a) The mathematical representative of P is a subset of the mathematical representative of Q. (3b) P implies Q — that is, whenever one can predict P with certainty, one can predict Q with certainty. (3c) For any statistical ensemble of systems, the probability of P is at most the probability of Q.)”[7]

伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼主张:“(3a)-(3c)的等价性使得人们将关于任何物理系统 G 的实验命题的数学表达的全体就视为 G 的命题演算的数学表达。(The equivalence of (3a)-(3c) leads one to regard the aggregate of the mathematical representatives of the experimental propositions concerning any physical system G, as representing mathematically the propositional calculus for G.)”[7]

伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼引入如下的公设:“公设:关于一个量子力学系统的任何两个实验命题的数学表达的集合论乘积,本身就是一个实验命题的数学表达。(POSTULATET: The set-theoretical product of any two mathematical representatives of experimental propositions concerning a quantum-mechanical system, is itself the mathematical representative of an experimental proposition.)”[7]

“如果将上述公设添加到量子理论的通常公设中,则可以推断出:任意两个[闭线性子空间]的集合积与闭线性和,以及希尔伯特空间中任何一个闭线性子空间的正交补,在数学上表达关于量子力学系统 G 的一个实验命题,其本身表达关于 G 的一个实验命题。(if one adds the above postulate to the usual postulates of quantum theory, then one can deduce that: The set-product and closed linear sum of any two [closed linear subspaces], and the orthogonal complement of any one closed linear subspace of Hilbert space representing mathematically an experimental proposition concerning a quantum-mechanical system G, itself represents an experimental proposition concerning G.)”[7]

于是,“这将关于 G 的实验命题的演算定义为具有三个运算和一个蕴涵关系的演算(This defines the calculus of experimental propositions concerning G, as a calculus with three operations and a relation of implication)”[7]

然后,伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼显示了量子力学的命题演算与抽象射影几何具有相同的结构[7]。

伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼定义的“量子力学的逻辑”的两个特征为:(1)排中律不成立(源于量子力学的概率本质,排中律原本就不成立);(2)逻辑演算的分配律不成立[7]。

“从数学上讲,量子力学可以看作是一种基于非经典命题逻辑的非经典概率演算。更具体地说,在量子力学中,每个形式为‘物理量 A 的值在范围 B 内’的概率命题都由希尔伯特空间 H 上的投影算子表示。它们形成了一个非布尔的 -- 特别是非分配的 -- 正交补格。量子力学状态与该格上的概率测度(适当地定义)完全对应。(Mathematically, quantum mechanics can be regarded as a non-classical probability calculus resting upon a non-classical propositional logic. More specifically, in quantum mechanics each probability-bearing proposition of the form ‘the value of physical quantity A lies in the range B’ is represented by a projection operator on a Hilbert space H. These form a non-Boolean -- in particular, non-distributive -- orthocomplemented lattice. Quantum-mechanical states correspond exactly to probability measures (suitably defined) on this lattice.)”[10]

“量子力学的逻辑”并非“量子逻辑学” -- 为什么“量子力学的逻辑”在本质上不同于经典数理逻辑学及其它哲学逻辑学?

“量子力学的逻辑(the logic of quantum mechanics)”当然可以被认定为一种关于量子力学的、具体的“逻辑”(因此,称其为“经验的”也无问题);但是,“量子力学的逻辑”并非一种抽象的“量子逻辑学(quantum logic)”(尽管有大量的文献表述它及其各种衍生为“quantum logic”),因为它既没有真正以关于量子现象的论证及推理作为研究对象亦没有为关于量子现象的论证及推理提供一般性的逻辑有效性判别标准。

伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼的先驱工作仅仅是将量子力学抽象化为其某种数学表达,然后尽可能地让这种数学表达对应于经典命题演算,最终得到了类似于经典命题演算之布尔格的非布尔(非分配的)正交补模格。所以,准确地说,伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼的工作就是对量子力学给出了一种数学/逻辑解释,并未对关于量子力学中的论证及推理建立起一个有坚实语义基础的、健全的、完全的逻辑系统,像经典数理逻辑学那样。

伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼在1936年论文的最后提出的问题,还在考虑实验命题逻辑演算的实验意义:“两个给定实验命题的并和交能赋予什么实验意义?(What experimental meaning can one attach to the meet and join of two given experimental propositions?)”[7] 实际上,伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼从未认为“量子力学的逻辑”[7]是完成了的工作,而是认为:“我也认为我们的论文不会非常详尽或具有结论性,但我们不应试图做到这一点:这个主题显然只是处于发展的开始阶段,我们更想提出这一发展的方向,而不是达到‘最终’结果。就我个人而言,我甚至不相信已经找到了量子力学的正确形式框架。(I, too, think, that our paper will not be very exhaustive or conclusive, but that we should not attempt to make it such: The subject is obviously only at the beginning of a development, and we want to suggest the direction of this development much more, than to reach ‘final’ results. I, for one, do not even believe, that the right formal frame for quantum mechanics is already found.)”[8]

多少有点极端地问一个问题,伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼在考案“量子力学的逻辑”时,他们用到的元逻辑为何?难道不是经典逻辑吗?

尽管作为伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼先驱工作的后续,不断有一些关于量子力学的所谓“量子逻辑”被提出,但是绝大部分(如果不是全部的话)是对伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼的“量子力学的逻辑”的某种补充或修正[9]。

众所周知,迄今为止,各种关于量子力学的所谓“量子逻辑”还未在量子力学研究中真正起到基础逻辑学的支撑作用。试图用“量子力学的逻辑”来“解决量子理论的主要物理和认识论难题(solving the main physical and epistemological difficulties of QT)”,甚至被认为“也许是一些量子逻辑先驱者的幻想(perhaps an illusion of some pioneering workers in quantum logic)”[9]。

普特南的主张

普特南的主张[5,6],归纳起来有如下三个要点[11]:

(a)“量子力学促使我们修改经典的逻辑的概念,转而采用‘量子逻辑的’概念。这可以通过类比几何来解释,广义相对论也促使我们修改欧几里得(或更确切地说是闵可夫斯基)几何概念,转而采用黎曼(或更确切地说是伪黎曼)几何概念。(Quantum mechanics prompts us to revise our classical logical notions in favour of ‘quantum logical’ ones. This is explained by analogy to geometry, in the sense that also general relativity prompts us to revise our Euclidean (or rather Minkowskian) geometrical notions in favour of Riemannian (or rather pseudo-Riemannian) geometrical notions.)” “逻辑学和几何学一样是经验性的。我们生活在一个非经典逻辑的世界里。(Logic is as empirical as geometry. We live in a world with a non-classical logic.)”[5]

(b)“这种逻辑学的修正不仅仅是局部的,即不仅仅是一个特别适合特定主题的逻辑系统的例子,而是真正全局的。量子逻辑是‘真正的’逻辑学(就像时空的‘真正的’几何是非欧几里得的一样)。事实上,我们迄今为止未能认识到我们通常的逻辑连接词是量子逻辑的连接词。(This revision of logic is not merely local, i.e. not merely an instance of a logical system especially suited to a particular subject matter, but it is truly global. Quantum logic is the ‘true’ logic (just as the ‘true’ geometry of space-time is non Euclidean). Indeed, we have so far failed to recognise that our usual logical connectives are the connectives of quantum logic.)” “由于对普特南来说,逻辑学很大程度上就是研究物理属性实际如何结合,因此他得出结论,经典逻辑完全是错误的:分配律不是普遍有效的。(Since logic is, for Putnam, very much the study of how physical properties actually hang together, he concludes that classical logic is simply mistaken: the distributive law is not universally valid.)”[14]

(c)“因此,认识到逻辑学是量子的就解决了量子力学的标准悖论,例如测量问题或薛定谔的猫。(Recognising that logic is thus quantum solves the standard paradoxes of quantum mechanics, such as the measurement problem or Schrodinger’s cat.)”

这里,请读者仔细注意笔者对英文原文“logic”一词分别依照文脉翻译成为“逻辑学”和“逻辑”的区别,这一点正是本系列文章[1-4]强调之关键;当然,笔者的翻译反映了笔者个人对“量子逻辑(quantum logic)”的认识,如同本文前一节所述。

普特南的上述激进主张当然引发了一场长时间的讨论[11-14]。

普特南的主张(c),可以说是个已经解决了的问题,经过广泛讨论,学界,包括普特南本人,都认为,即便是基于“量子逻辑”,也无法解决量子力学的悖论难题[11]。笔者个人认为,这恰恰显示了所谓“量子逻辑”的“无能”,并非真正能够作为基础逻辑学来支撑量子力学。

关于普特南的主张 (a),在把所谓“量子逻辑”视为一个局部的、具体/经验的“逻辑”的前提下,似乎不少学者都可以接受其合理性[11]。

而普特南的主张 (b),将“量子逻辑”视为“真正的”逻辑学(应该是相当于“the one true logic”,“the one right logic”),是最具争议的主张,似乎没有得到过广泛认可[11]。比如,英国哲学家达米特(Michael Anthony Eardley Dummett, 1925-2011)就专门撰文指出,普特南如果不接受经典逻辑就无法接受现实主义,因此他因为量子现实主义而支持量子逻辑的论点是无望的[11,12]。

实际上,普特南一方面主张逻辑学可以是经验的,根据量子力学的经验应该改造传统的逻辑学,另一方面又主张根据量子力学的经验,“量子逻辑”才是“真正的”逻辑学。这两种主张,如果从“逻辑”与“逻辑学”的关系,或者其本人主张的“局部”与“全局”的关系来看,似乎在概念上本身就相互矛盾。普特南本人应该也认识到自己文章[5]中所主张的有问题,在文章被收入文集中时,专门修改了文章的题目,居然用了伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼1936年论文同样的题目![5]。

“相关量子逻辑”或“量子相关逻辑”

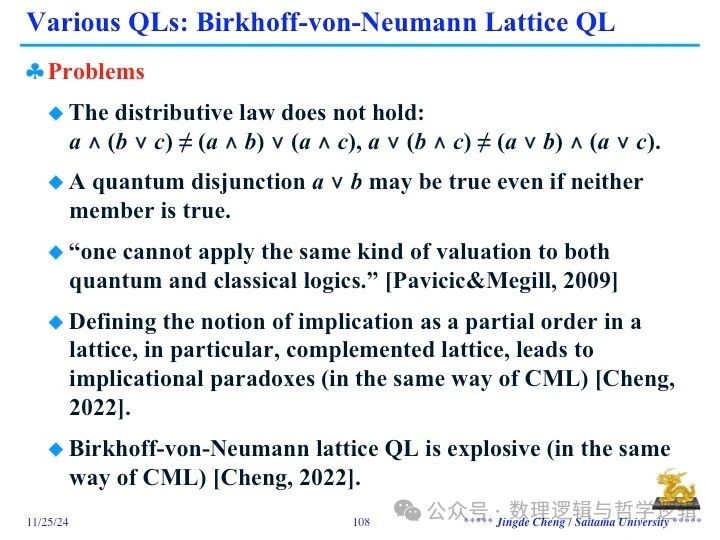

最后,笔者应该顺带指出的一点是:伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼的“量子力学的逻辑”以及后续的各种所谓“量子逻辑”都原样保留着经典数理逻辑中的条件句表达,实质蕴涵,将其定义为代数格中的偏序关系。只要一个“量子逻辑”以偏序关系来表达条件句/蕴涵关系并且以正交补的正交模格作为其代数解释/结构,那么它就一定满足关于蕴涵悖论的Sugihara标准,因此一定是一个具有蕴涵悖论的逻辑系统[15-17]。实际上,伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼的文章第8小节(定义格)第一句话就是:“In any calculus of propositions, it is natural to imagine that there is a weakest proposition implying, and a strongest proposition implied by, a given pair of propositions.”[7](说明一下,此处该文章中“weakest”和“strongest”两个词的用法与逻辑学界的通常用法相反) 从伯克霍夫和冯诺依曼试图将刚刚被完全形式化的“崭新”的经典数理逻辑作为建立“量子力学的逻辑”时的比照对象的历史观点来看,这也是一个理所当然的结果。

笔者认为,如果要建立真正的“量子逻辑学”,使其真正成为量子力学的逻辑基础以支撑量子力学研究中的科学发现与预测,那么对当前的所谓“量子逻辑”进行“相关化”(或者对相关逻辑进行“量子化”)是必不可少的[15-17],更深入的讨论超出本文范围了。

参考文献

[1] 程京德,“‘逻辑’与‘逻辑学’(1) -- 起源、定义、异同”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2024年10月12日;“‘逻辑’与‘逻辑学’(1) -- 起源、定义、异同(增补版)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,2024年11月10日。

[2] 程京德,“‘逻辑’与‘逻辑学’(2) -- 欧美名人的‘逻辑/逻辑学’用例”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2024年10月23日。

[3] 程京德,“‘逻辑’与‘逻辑学’(3) -- 中国名人的‘逻辑/逻辑学’用例”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2024年10月31日。

[4] 程京德,“‘逻辑’与‘逻辑学’(4) -- “逻辑学”是怎样的一门科学?”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2024年11月5日。

[5] H. Putnam, “Is Logic Empirical?” in R. Cohen and M. Wartofsky (eds.), “Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science,” Vol. 5, pp. 216-241, 1968; Reprinted as “The logic of quantum mechanics,” in H. Putnam, “Mathematics, Matter, and Method - Philosophical Papers, Volume 1,” pp. 174-197, Cambridge University Press, 1976, 1979(2nd Edition).

[6] H. Putnam, “How to Think Quantum-Logically, Synthese, Vol. 29, pp. 55-61, 1974; Reprinted in P. Suppes (ed.), Logic and Probability in Quantum Mechanics, pp. 47-53, 1976.

[7] G Birkhoff and J. von Neumann, “The Logic of Quantum Mechanics,” The Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 823-843, 1936.

[8] M. Redei, “The Birkhoff-Von Neumann Concept of Quantum Logic,” in K. Engesser, D. M. Gabbay and D. Lehmann (Eds.), Handbook of Quantum Logic, Elsevier, pp. 1-22, 2009.

[9] M. L. D. Chiara and R. Giuntini, “Quantum Logics,” in D. M. Gabbay and F. Guenthner (Eds.), “Handbook of Philosophical Logic, 2nd Edition,” Vol. 6, pp. 129-228, Springer, 2002.

[10] A. Wilce, “Quantum Logic and Probability Theory,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University, 2002-2021.

[11] G. Bacciagaluppi, “Is Logic Empirical?” in K. Engesser, D. M. Gabbay and D. Lehmann(Eds.), Handbook of Quantum Logic, Elsevier, pp. 49-78, 2009.

[12] M. Dummett, “Is Logic Empirical?" in H. D. Lewis (Ed.), Contemporary British Philosophy, 4th series, pp. 45-68, 1976.

[13] K. Engesser, D. M. Gabbay and D. Lehmann, “Editorial Preface,” in K. Engesser, D. M. Gabbay and D. Lehmann (Eds.), Handbook of Quantum Logic, Elsevier, 2009.

[14] C. de Ronde, G. Domenech, and H. Freytes, “Quantum Logic in Historical and Philosophical Perspective,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[15] 程京德,“现代逻辑之未来 – 从相关逻辑到量子逻辑(纲要)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2023年7月25日。

[16] 程京德,“悖论集锦(2) – 作为逻辑学中最大难题的蕴涵悖论问题(上)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2024年3月18日;悖论集锦(2) – 作为逻辑学中最大难题的蕴涵悖论问题(上)(修订增补版)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,2023年4月11日;“悖论集锦(2) - 作为逻辑学中最大难题的蕴涵悖论问题(下)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2024年4月18日。

[17] 程京德,“强相关逻辑及其应用(上)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2023年6月18日; “强相关逻辑及其应用(中)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2023年8月8日; “强相关逻辑及其应用(下)”,微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”,科学网博客,2023年8月12日。

微信公众号“数理逻辑与哲学逻辑”

https://blog.sciencenet.cn/blog-2371919-1461498.html

上一篇:何谓“计算机”?

下一篇:哲学逻辑(3) – 量子逻辑学(Quantum Logic)